Online Exhibition: Famous Victorians

Religious leaders

During the later Victorian period, perhaps as a reaction against the scientific controversies of the time, there was a revival of interest in religion. At one extreme this was expressed in the High Church Oxford Movement, led by John Keble, who fought for the rights of Catholics and the need for worship to restore a sense of reverence John Newman, (1801-1890) tried to show that the Church of England had always steered a middle course between protestant fundamentalism and Catholicism. He converted to Catholicism in his later years and became a Cardinal. Supporters of the group, J. M. Neale and B. Webb, developed an interest in church architecture and in religious ritual.

By contrast fundamentalism became popular too and there was growing support for Evangelicalism, which stressed literal belief in the Bible and that people could only be saved from hell by believing in God. Preachers like the Baptist minister C. H. Spurgeon (1834-92) became very popular, and their sermons could be bought as pamphlets and in books. Although many people belonged to the Church of England, there were many other denominations such as the Baptists and Methodists which grew in popularity during the period, and several new denominations such as the Salvation Army and the Plymouth Bretheren were founded.

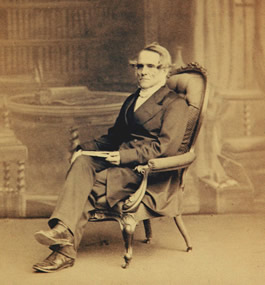

Frederick Dennison Maurice (1805-1872)

FD Maurice, as he was known, was the founding father of the Christian Socialist movement. Educated at Trinity College, Cambridge, he wrote articles whilst a student for The Metropolitan Quarterly Magazine and The Westminster Review. He later became editor of the well respected journal The Athaneum.

Maurice thought it was wrong that different types of Christians should dislike each other so in his most important book, The Kingdom of Christ (1838) he argued that each denomination held their own particular

part of the truth, and should be listened to and treated as equals. He also argued that it was important for Christians to be involved in politics and to try to improve the social conditions of those around them. He was strongly in favour of improving education for the poor and for those who did not agree with the Church of England and so were not allowed to attend Universities.

Maurice was made a professor of religion at King's college London in 1840. People in England had been shocked by the French revolution and were afraid that the poor in England might rebel. Maurice formed the Christian Socialist movement with his friends the writers Charles Kingsley and Thomas Hughes. It was designed to be an alternative to the humanistic socialism of the day, and to help the poor without causing a revolution.

However people thought that this sounded very dangerous, and Maurice was forced to resign his professorship in 1853. He helped start the London Working Man's College in 1854 and in 1866 he was appointed Professor of Moral Philosophy at Cambridge University.

Frederick Dennison Maurice. From Portraits of Men of Eminence vol 1 p141